Table of Contents

SUMMARY

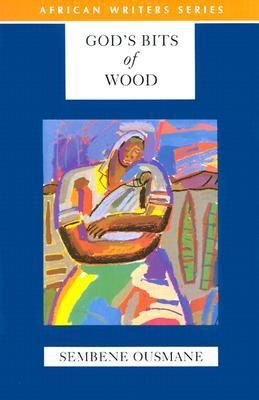

The novel is set in pre-independence Senegal and follows the struggles of the African train workers in three cities as they go on strike against their French employers in an effort for equal benefits and compensation. The chapters of the book shift between the cities of Bamako, Thies, and Dakar and track the actions and growth of the men and women whose lives are transformed by the strike. Rather than number the chapters, Ousmane has labeled them by the city in which they take place, and the character that is the focal point of that chapter.

As the strike progresses, the French management decides to “starve out” the striking workers by cutting off local access to water and applying pressure on local merchants to prevent those shop owners from selling food on credit to the striking families. The men, who once acted as providers for their family, now rely on their wives to scrape together enough food in order to feed the families. The new, more obvious reliance on women as providers begins to embolden the women. Since the women now suffer along with their striking husbands, the wives soon see themselves as active strikers as well.

The strategy of the French managers, or toubabs as the African workers call them, of using lack of food and water to pressure the strikers back to work, instead crystallizes for workers and their families the gross inequities that exist between them and their French employers. The growing hardships faced by the families only strengthens their resolve, especially that of the women. In fact, some of the husbands that consider faltering are forced into resoluteness by their wives. It is the women, not the men, who defend themselves with violence and clash with the armed French forces.

The women instinctively realize that women who are able to stand up to white men carrying guns are also able to assert themselves in their homes and villages, and make themselves a part of the decision making processes in their communities. The strike begins the awakening process, enabling the women to see themselves as active participants in their own lives and persons of influence in their society.

PLOT

The action takes place in several locations primarily in Bamako, Thiès, and Dakar. The map at the beginning shows the locations and suggests that the story is about a whole country and all of its people. There is a large cast of characters associated with each place. Some are featured players—Fa Keita, Tiemoko, Maimouna, Ramatoulaye, Penda, Deune, N’Deye, Dejean, and Bakayoko. The fundamental conflict is captured in two characters: Dejean, the French manager and colonialist, and Bakayoko, the soul and spirit of the strike. In another sense, however, the main characters of the novel are the people as a collective and the railroad itself.

The strike causes an evolution in the self-perception of the strikers themselves, one that is most noticeable in the women of Bamako, Thiès, and Dakar. These women go from merely standing behind the men to walking alongside them and eventually marching ahead of them. When the men are able to work the factory jobs that the railroad provides them, the women are responsible for running the markets, preparing the food, and rearing the children. But the onset of the strike gives the role of bread-winner – or perhaps more precisely, bread scavenger – to the women. Eventually it is the women that march on foot for over four days from Thiès to Dakar. Many of the men originally oppose the women’s march, but it is precisely this show of determination from the marching women, who the French had earlier dismissed as “concubines”, that makes the strikers’ relentlessness clear. The women’s march causes the French to understand the nature of the willpower that they are facing, and shortly after the French agree to the demands of the strikers.

The book also highlights the oppression faced by women in the colonial era. They were deprived of their ability to speak on matters including society as a whole. Sembène, however, raises women to a higher spectrum by considering them equally important.

THEMES

Humanity versus Machine

The novel’s three main themes are closely intertwined with each other. If there is a primary among the three, it is the exploration of the relationship between machine and humanity, machine in this context being defined in two different ways. The first is more literal, the railway “machine” (its rails, engines, cars, maintenance shops) which, in turn, is part of the larger industrial “machine” that began to dominate and define the human condition in the mid to late eighteenth century and continued its dominance well into the twentieth century. This “machine” is portrayed as simultaneously demanding and nurturing, dominating and essential, providing a way of life and security for those who work to maintain it. Several times throughout the narrative characters, even the striking ones; refer to the value and necessity of the “machine” in their lives, and their gratitude for it.

CHARACTERS

Beaugosse (Daouda): educated; in love with N’Deye touti; quits union and RR and allies with company. (‘Beaugosse’ means ‘pretty boy’, or ‘dandy’, in French, but without the homosexual overtones these words have in English. In other words, somebody ‘dressed to impress’).

Deune: husband of Bineta and Mame Sofi.

Ramatoulaye: Head of large family clan centered at her ‘compound’, N’Diayene. Sister of El Hadji Mabigue.

Houdia M’Baye: widow of Badiane (killed in first fighting in strike); 9 children including Anta; Abdou; N’Dol; Strike.

N’Deye Touti: member of Ramatoulaye’s household (calls Rama “aunt”). Educated; in love with Bakayoko. One of the central characters of the novel.

Minor characters

Abdoulaye: head of Dakar section of CGT (the French trade union confederation, like the AFL-CIO, only heavily, though not exclusively, Communist).

Imam: Muslim priest; strongly with company and French and anti-strike.

Deputy-Mayor: African mayor who is puppet of French; one of members of French National Assembly (=Congress, or Parliament); for French, against strike.

Point of View

The story is told from the third person, past tense, omniscient point of view. This means it recounts actions, events, and circumstances from a variety of perspectives, weaving together a multi-textured tapestry of emotional colors and experiences that combine to create a complex, yet thematically unified, narrative portrait of individual and societal transformation. There are two principal benefits to this emotionally and spiritually panoramic point of view. The first is to create a strong sense that in spite of differences in individual circumstance, the journeys of the various characters are all essentially the same. As discussed above, some of these journeys are more inwardly directed (Bakayoko, N’Daye Touti, Mamadou Keita, Maimouna) while others are more outward (Ramatoulaye, Penda). All, however, are ultimately defined by movement towards strength, self awareness, courage, and connection to a spiritual, humanist truth.